A World Without Work by Daniel Susskind

BOOK REVIEWS BY BINOD

BINOD’S RATING: 7.5/10The economist Robert Skidelsky wrote that fears of technological unemployment were not so much wrong as premature: “Sooner or later, we will run out of jobs.”

The title of Daniel Susskind’s book, therefore, is like a reiteration. Susskind has come up with an explainer rather than a polemic, written in the relentlessly reasonable tone of a clever, sensible man telling you what’s what.

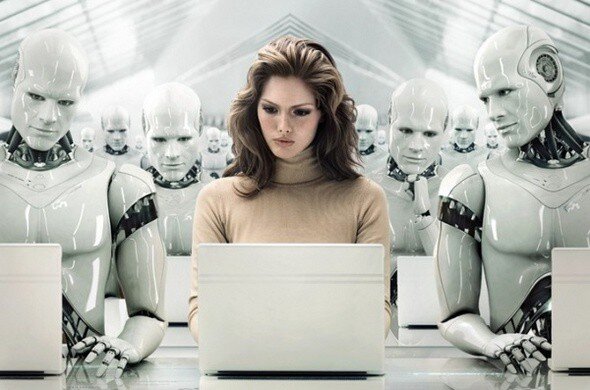

Susskind’s thesis — that we are heading towards a world in which human work will become obsolete — is built on the idea that most of the conventional notions about AI learning have been wrong.

“Automation of jobs is one of the greatest questions of our time”

Key points

The book provides a brilliant discussion of the two main economic forces that determine whether there is technological unemployment: the harmful substitution force and the helpful complementary force.

The substitution force is machines replacing humans in jobs if they are cheaper, better, and / or faster. Despite numerous rounds of automation (mostly mechanisation so far) humans have not been ejected from the workplace. Hence our complacency.

The complementary force has three effects. The productivity effect is when automation eliminates some jobs but makes other workers more productive e.g. Computer-aided design. The bigger pie effect is the story of US GDP being 15,000 times higher in 2000 than it was in 1700 and this means more wealth, more demand, and more jobs. The changing pie effect is the shift in economies and employment from farms to factories, and then to offices.

So far, the helpful Complementary Force has been stronger than the Substitution Force. But it is much harder to argue that the complementary effect will persist for the foreseeable future. Machine learning enables machines to carry out tasks which are non-routine, and sometimes even require creativity. Example? The clear evidence of creativity in the famous move 37 in game two of AlphaGo’s defeat of Lee Sedol, the best human Go player.

Susskind takes the reader through fascinating junkyard of discredited assumptions about technological unemployment. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, automation tended to replace human labour in “routine” tasks without destroying entire occupations. Even when certain professions were eliminated, new ones were created.

But AI has changed everything, starting with the definition of “routine”. Time and time again, it has been assumed that a task required a human being until a machine has come along and proved otherwise, and WITHOUT needing to mimic human cognition. It used to be argued that workers who lost their low-skilled jobs should retrain for more challenging roles, but what happens when the robots, or drones, or driverless cars, come for those as well? Predictions vary but up to half of jobs are at least partially vulnerable to AI, from truck-driving, retail and warehouse work to medicine, law and accountancy.

Many of the boundaries economists and computer scientists developed for thinking about what machines could and couldn’t do have been CROSSED. For example, driving a car, making a medical diagnosis or identifying a bird from a fleeting glimpse. All these tasks can now be accomplished by software now.

We thought many of these tasks would be difficult to automate because humans couldn’t articulate how they performed them. They relied on experience, intuition and gut reaction and the argument was how could you write a set of instructions for a computer to follow? But by using lots of data and computing power, machines are creating new strategies, strategies that are new to humans! Machines are no longer riding on the coattails of human intelligence.

Many wrongly assume that machines will have to go beyond Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI) which is specific task focused and that they will have to attain artificial general intelligence (AGI) to be capable of the more complex things that we do, like driving, diagnosing cancers, holding conversations, etc. The shock is that technological unemployment only needs task encroachment based on ANI and hence does NOT require AGI.

Susskind expects task encroachment to cause two kinds of unemployment: frictional, and then structural. Frictional technological unemployment means there are still jobs, but not all of us are equipped to do them. Structural technological unemployment means the complementary force has become ineffective; a human is replaced in one job, and even though the productivity effect, the bigger pie effect or the changing pie effect means that another job is created, that new job is done by a machine, not by the displaced human.

But forecasting which jobs and tasks will be automated is hard. Should people bother training to be doctors or lawyers when automation is already encroaching on these careers? For young professionals, Susskind says the best thing to do is pursue the traditional path but be far more agnostic and open minded along the way about opportunities that come up. Take the systems developed by DeepMind or the ones that recognize melanomas by Sebastian Thrun’s team at Stanford – these teams contain lots of domain experts, such as trained doctors.

The state will need to smooth this painful transition. Perhaps initiate a conditional universal basic income funded by taxes on capital to share the proceeds of technological prosperity. The available work will also need to be more evenly distributed.

“Nothing is certain in life except death, taxes, and the relentless process of task encroachment.”

But the challenge of a world without work isn’t just economic but political and psychological. Joblessness tends to create loneliness, lethargy and social dysfunction. Because work not only gives people income, but often gives meaning and identity. “What do you do for a living?” is for many people the first question they ask when meeting a stranger, and there is no entity more beloved of politicians than the “hard-working family”. How can people get meaning in future with less work?

One way is to think of this as NOT being about the future of work, but the future of leisure. We have labour-market policies. Perhaps we also need leisure policies to shape how people spend their spare time. We can’t educate ourselves out of the problem, at least not as we currently envision it. Neither bolstering STEM skills nor pushing liberal arts addresses the bigger issue, which is that we need an education system that isn’t only geared up to teach people how to enter the world of work, but rather how to make leisure productive.

It’s not all doom and gloom. Susskind says the below residual tasks will remain for humans:

1) Tasks that prove impossible to automate.

2) Tasks that are possible but unprofitable to automate.

3) Tasks that are both possible and profitable to automate but remain restricted to human beings due to regulatory or cultural barriers that societies build around them.

What I liked

He writes with such elegance that you don't notice how much you're learning. Elegant, original and compelling.

Hype-free, jargon free perspective.

His analysis doesn't focus narrowly on economics. He addresses the broader societal concerns e.g. how individuals can share prosperity and sustain a feeling of self-worth when traditional skills are devalued.

Lucid and relentlessly logical approach to this complex and critical topic. He quickly and deftly breaks down a complex question into its component parts. I loved the substitution vs complementary force analysis.

This is interesting reading if only for the intriguing history lessons. He always has a helpful graph to hand and a great collection of anecdotes about technology and society, from Ned Ludd to Deep Blue via the 1890s horse manure crisis.

What I didn’t like

There is one big gap in the book: China. China is lab for all the changes Susskind talks about — from robots replacing cheap and even higher-end labour, to the promise and perils of AI, to the ability of the state to buffer them. If there’s one place where science fiction is already reality, it is China.

Conclusion

This time it’s likely to be different. Although the dire predictions of workers losing their jobs to machines have not come true in the past, that doesn’t mean they never will.

The book is a timely alarm call, and we should think of how to prepare for a possibly messy future.

Dr. Daniel Susskind is a Fellow in Economics at Balliol College, Oxford University, England. He is a teacher and researcher who explores the impact of technological advancement on work and society. He is the co-author of the best-selling book, The Future of the Professions.